A Place is its History: Exploring Famous Sites in Philadelphia

Philadelphia is one of America's most important historical cities. That history is specifically preserved and presented in an area of the city called “Historic Philadelphia,” where museums and architecture celebrate and document the past. Although the works of art included in “A Sense of Place” at the Arthur Ross Gallery are modern Japanese prints, many of the questions and themes explored in the exhibition are easily transferable to other famous places, including Philadelphia. What makes a place famous? How do people promote a site as a famous place?

As residents of Philadelphia, a city rich with famous places, the members of our spring curatorial seminar became local tourists and prepared short presentations on eight sites around the city: the Walnut Street Theater, Independence Hall, the Philosophical Society, Benjamin Franklin’s Grave, the Arch Street Quaker Meeting House, the Betsy Ross House, Elfreth’s Alley, and the City Tavern. Each student visited the site, researched its online presence, and evaluated how each place is presented as “famous.”

On April 18th 2015, the class went on a walking tour of Philadelphia during which each student presented his or her site. The text of those presentations appears below. You will also find images from our adventures around Philadelphia.

The Walnut Street Theater

825 Walnut Street

Standing at the corner of Ninth and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia for 200 years, the Walnut Street Theater, a national historical landmark, has housed two centuries' worth of American popular entertainment. The Walnut remained a significant player on the American theater scene throughout the twentieth century, and it was home to many pre-Broadway tryouts of plays that would go on to become American classics. Several famous American actors have performed here at the Walnut, including the Marx Brothers, Helen Hayes, Jessica Tandy, Edwin Forrest, Lauren Bacall, and many more.

Originally, when the theater opened its doors on February 2, 1809, it served as an equestrian circus. But the theater’s career as an equestrian circus did not last long. By 1812 the building had been converted to a legitimate theater—and the circus ring was replaced by a stage. President Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette were in attendance on the opening night of The Rivals, the Walnut’s first theatrical production in 1828.

In 1837, an 80-foot dome was added to the theater, making it the tallest structure in Philadelphia at that time. A place of many “firsts,” the Walnut was the very first theater to install gas footlights and air conditioning in 1855. (Notably, the first copyright law protecting an American play had its roots at the Walnut!) During the 1880s, the Walnut underwent many renovations, including a new stage for more elaborate musical comedies. In 1920, the interior was again rebuilt within the old exterior using structural steel in a design by William H. Lee.

The Walnut Street Theater’s rich history is evident backstage as well, as it is one of only a few remaining hemp housing in the country. To this day, it continues to operate with the original grid, rope, and sandbag system that was in use nearly two centuries ago.

In 1964, the Walnut Street Theater was designated as a National Historical Landmark. Five years later, it was renovated to become a performing arts center to include variety of live entertainment, such as A Man For All Seasons.

by Jenny Lu, University of Pennsylvania

Independence Hall

520 Chestnut Street

If you were ever enrolled in an American elementary school, you probably know something about Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, the original home of the Liberty Bell and the place where the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution were signed. The most ambitious public project of its time, this Georgian style building was designed by Andrew Hamilton and constructed between 1732 and 1753. Over the years the building has undergone many restorations including steeple additions and removals and complete overhauls of its interior design. The only remaining, original part of the building is the exterior of the central portion. Despite these numerous changes, today the building appears as it did in 1776, preserving the building’s first history as the place where the nation’s founding father’s met, debated, and declared independence.

This restoration of the site is important for several reasons. In her book Independence Hall in American Memory (2002), Charlene Mires persuasively argues that the emphasis placed on the building’s original identity (from textbooks to tourist pamphlets), obscures the more dynamic, evolving history of the building as a state capital, cultural center, courthouse, political arena, and site of civil disobedience. These other histories, in Mires’ view, have largely been neglected in favor of an idealized vision of America’s founding.

On a recent show, Bill Maher discussed a related debate concerning how American history is taught. Some schools districts in this country have recently argued that the best model is to not include too many negative views of American’s past. Bill Maher responded to this revisionist curriculum by pointing to the fact that most of the progressive and positive events in our nation’s history occurred in reaction to grievous errors, i.e. abolition in response to slavery, women’s suffrage in response to legal discrimination, child labor laws in response to indentured servitude. In other words, acknowledgement of the best requires knowledge of the worst. Similarly, the focus on Independence Hall as the “birthplace of America” conceals much of its history as well as the history of the nation it represents. For example, choosing not to remember the building as the site of Frederick Douglass’s 1844 speech on liberty turns a blind-eye to America’s history of slavery as well as it’s abolition of slavery.

As Charlene Mires’ research has shown, Independence Hall has many such “forgotten histories.” For example, in 1912 the city government of Philadelphia ruled that Independence Square could only be utilized for officially sanctioned, “patriotic” events. To quote from the film Dr. Strangelove (1964), this city law was effectively like saying: “You can't fight in here! This is the War Room.” Free speech was not restored to the home of “independence” until 1947 when this law was ruled unconstitutional.

by Anna Moblard Meier, Bryn Mawr College

The American Philosophical Society

105 South 5th Street

Have you ever thought of a place that connects art and science?This is American Philosophical Society (APS) situated in the Old City of Philadelphia that our curatorial team visited during a cold afternoon in March. Being the oldest learned society in the United States, APS was founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin and his friends to expand and promote knowledge. For two decades the APS’s members were meeting in various locations until they received a place at 104 South Fifth Street. The Federal style design of Philosophical Hall belongs to Samuel Vaughan, an English merchant and political activist. Later the architecture of the Hall inspired artist Frank H. Taylor to include it in the series "Old Philadelphia" prints, (1915-27).

The membership of APS reveals its high status: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Rush, Thomas Paine, David Rittenhouse, Charles Darwin. The Society was always progressive for the time. In 1789, it elected the first woman, Russian Princess Yekaterina Romanova Vorontsova-Dashkova.

In the 21st century, the American Philosophical Society continues to sustain the initial mission. It honors renowned scientists and scholars, supports research, and provides accesses to the collections. The American Philosophical Society Museum, that currently occupies Philosophical Hall, preserves a rich collection of rare books, manuscripts, works of art as well as it yearly hosts thematic exhibitions and contemporary art projects to connect art and science in Philadelphia.

by Daria Melnikova, University of Pennsylvania

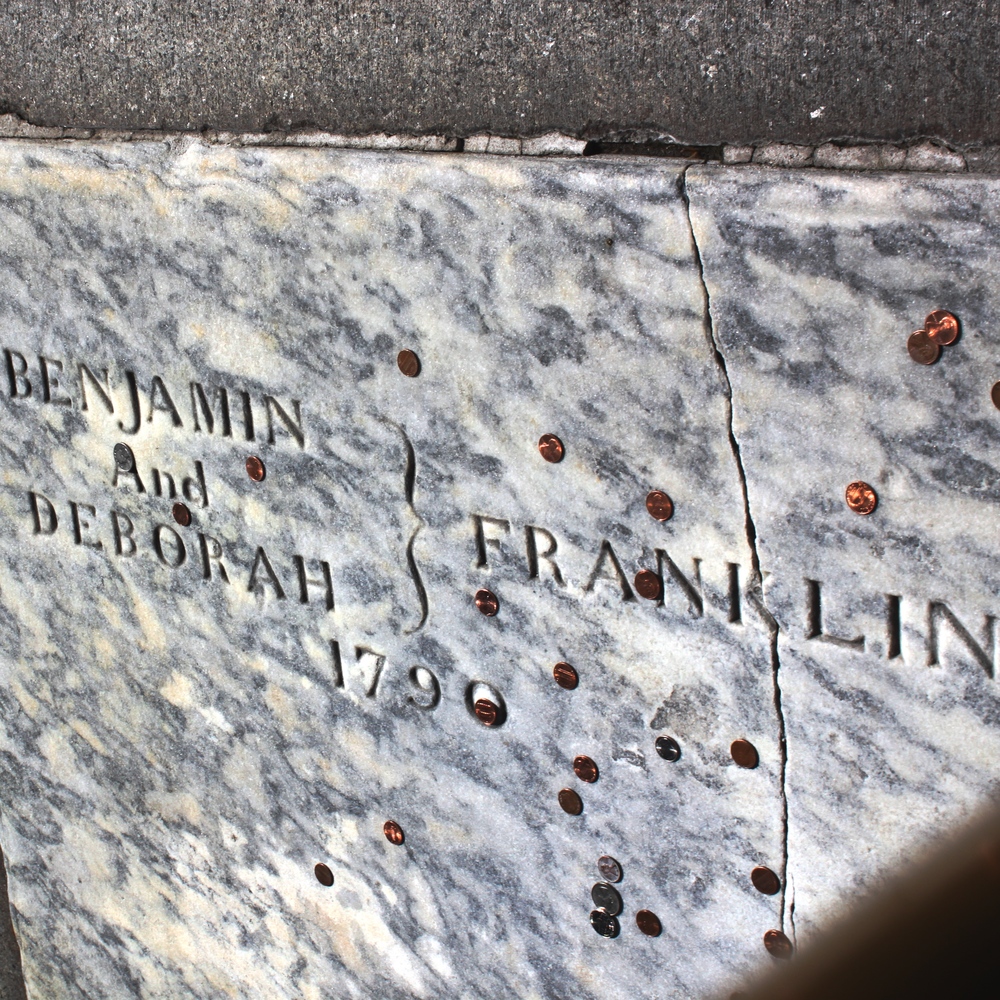

Benjamin Franklin's Grave

20 North American Street

In 1719, Philadelphia’s Christ Church purchased the nearby burial ground, a plot of land that would become Benjamin Franklin's final resting place. Although interments were made not long after the ground was laid out, the oldest inscription on grave stones dates from 1721. At the northwest corner of the ground lies the grave of Benjamin Franklin, his wife Deborah, and their son Francis F., their daughter Sarah Bache, and also the graves of John Read, Mrs. Franklin’s father; and Richard Bache, Franklin’s son-in-law. The plain stone that covers their resting-place reflects his character better than any epitaph, and the simple inscription affords abundant scope for meditation. The locality of the tomb is in a retired part of the grounds, and the grave until recently could only be visited with difficulty; but in the year 1858 a portion of the brick wall was removed, and an iron railing substituted, at this point, so that the historic grave of Franklin’s might easily be seen from the street.

On September 1st, 1730, Ben Franklin married Deborah Read, in whose father’s house he had boarded when he first came to Philly. All authorities unite in concluding that the marriage was without ceremony and was what is known as a common-law marriage. Franklin is said to have had two legitimate and two illegitimate children, but as he and his wife spoke of all of them as “Our Children,” Charles Henry Hart (infra) has concluded that Dr. and Mrs. Franklin were the natural parents of the children referred to as illegitimate ones, of whom William Franklin, the Loyalist Governor of New Jersey, was one. The son born after his marriage was Francis Folger Franklin, who died of smallpox at the age of four, and his youngest daughter, Sarah, married Richard Bache.

Ben Franklin died on April 17, 1790, of an attack of pneumonia, said to have been brought on by his insistence of exposing his body to the “fresh air.” His funeral was attended by twenty thousand people who followed his coffin to Christ Church Burial Ground.

The plain appearance of the tomb must strike everyone as unworthy of the memory of Franklin, over whose remains one would naturally look for an imposing monument commemorative of his worth; but the stone as seen here is such as was contemplated by him before his death, and particularly ordered in his will.

After Franklin’s death the following epitaph, written by himself, was found among his paper: “The body of Benjamin Franklin, printer (like the cover of an old book, its contents torn out, and tripped of its lettering and gilding), lies here, food for worms; but the work shall not be lost, for it will (as he believes) appear once more in a new and more elegant edition, revised and corrected by the Author.”

by Olivia Pei, University of Pennsylvania

Arch Street Quaker Meeting House

Arch Street Quaker Meeting House

320 Arch Street

William Penn gave this land to the Quakers (also known as the Religious Society of Friends) for use as a burial ground in 1701. The Arch Street Meeting House was erected in 1804 on top of the burial ground. Penn, one of the most important figures in early American history, was a Quaker himself, though this particular building was constructed well after his death in 1718.

West wing of the Arch Street Meeting House

One of a series of dioramas depicting events in William Penn's life and his contributions to the new colony of Pennsylvania

To a lesser degree, the Arch Street Meeting House also celebrates Philadelphia Quakers’ involvement throughout American history in efforts to promote peace and the equality of all men and women. A cutout of Lucretia Mott, for instance, stands beside the entrance desk. Mott was a local Quaker involved in the abolitionist movement, the movement for women’s rights, and antiwar activities during the nineteenth century.

The building is so large because, in addition to hosting weekly worship, regional congregations gathered here once a year for a business meeting. Originally, it had two separate but identical meeting rooms, one for women and one for men. Quakers believe in the equality of all people, so this division of men and women was not meant to suggest inequality of the sexes. Instead, they were afraid that women would not speak up in the presence of men, and thought having two rooms for business meetings would make the women more comfortable. By the standards of 1804, each room could seat a thousand people. In 1954, the men’s room, in the east wing of the building, was converted into a space for dining and exhibitions. The west wing, or women’s meeting room, still looks much as it did in the nineteenth century and is still used for the yearly business meetings. In keeping with Quaker aesthetics, it is furnished simply with benches and few decorative flourishes, though large windows let in a good amount of light.

Some sort of fence around the site has been present since 1701, and the current fence was begun in 1795. Quakers don’t mark their graves, so the fence originally made it clear where the burial ground was actually located.

Why is this a famous place?

As the Arch Street Meeting House presents itself, a large portion of its fame stems from its association with William Penn. At the front desk, two out of five available brochures discuss Penn, and a third talks about the importance of freedom of religion in Pennsylvania, the colony that Penn established. Furthermore, half of the exhibition space in the east wing is dedicated to dioramas depicting important events in his life, and a series of plaques quote his writings. It was important to Penn that the laws of his new colony protect residents’ freedom to worship as they pleased, a rare privilege at the time and one that Quakers had not enjoyed in England. Later, aspects of Penn’s Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges would inspire the U.S. Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights.

How does it draw attention to itself?

One special thing about the Arch Street Meeting House is that it has been continuously used for Quaker meetings since its construction in 1804. For this reason, the building carries a degree of historical authority that many other sites cannot match. However, it also means that the Meeting House can't sell itself as a straightforward tourist attraction and must keep its religious function in mind in its self-presentation.

To prepare for this presentation, I visited the site with my fellow classmate Kendra. Beforehand, we visited the the Betsy Ross House, the historic place that was the subject of her report. The Betsy Ross House served as an interesting foil for the Arch Street Meeting House. From the street, one notices that both have Pennsylvania historical markers outside, though the Meeting House is lacking the city’s more noticeable red, white, and blue marker and instead uses signage of its own creation in subtle colors and fonts that are in keeping with Quakers’ simple aesthetic. All the gates in the brick fence are kept open and are marked with signs; otherwise, I imagine the site might seem unapproachable thanks to its high walls and low-key appearance without banners or other advertisements.

Generally speaking, the Meeting House takes a more passive approach to attracting tourists than the Betsy Ross House, as is apparent in its admission fee structure, gift shop, and self-promotion. The Meeting House suggests a $2 donation on its website, but no one mentioned the donation once in the building. Since its primary function is still religious, the Meeting House also does not have corporate sponsors, unlike the Betsy Ross House. As for souvenirs, the Meeting House does sell a few publications and trinkets related to Quakerism, but the for-sale section mostly seems like an afterthought. The Betsy Ross House, meanwhile, has a top-notch gift shop that is nearly as large as the first floor of the house itself, which again suggests the importance of visitors and the income they generate to the functioning of that site. The Meeting House, as a still-operational religious institution, would presumably exist whether it was visited by tourists or not. Perhaps because its sole function isn’t catering to visitors, some of the displays, like the dioramas of Penn’s life, seem slightly out of date in our digital world. In thinking about this particular place as a historical site, I also wanted to know more about the Meeting House and a bit less about Penn. For many visitors, Penn is the quintessential Quaker, and--in this most quintessential of Quaker places--the information provided responds to the public’s interest in him. However, Penn died almost a century before this building was even constructed. To me, in thinking about the Meeting House as a historical site, the most relevant displays were those about its construction and how ordinary Quakers who attended meetings here lived and thought.

East wing of the Arch Street Meeting House

As might be expected, in sources of information for sightseers, like the official visitphilly.com website, the Arch Street Quaker Meeting House and other religious buildings that are still in use don’t seem to pay to promote their listings. However, they still appear on most free maps and pamphlets like “Beyond the Bell,” which is published by Philadelphia’s Historic Neighborhood Consortium. There is also a special series of signs erected by the “Old Philadelphia Congregations,” a group of churches and synagogues, to draw attention to this and other still-functioning sacred spaces.

To return to the interior of the Meeting House, when one first enters, one is greeted by a tour guide by the front desk. The website states that if you call ahead to arrange a tour, your guide can focus on various topics of your choosing. However, if you just show up—especially on a quiet weekday, as Kendra and I did—the tour is casual. Even though it was just the two of us, we were shown around immediately rather than forced to wait until a larger group formed. In the final room we visited, the east meeting room, we sat across from our guide at a table and she let us ask anything we liked, answering many questions about the worship services based on her own personal experience as a Quaker.

I found the unscripted, dialogue-like quality of the tour surprising—I hadn’t expected to hear so many anecdotes drawn from our guide’s own experience of Quaker religious life, nor to speak so much myself. The tour and other aspects of the Arch Street Meeting House’s presentation reflect the balance the institution tries to strike between being a tourist destination that aims to impart historical knowledge and a still-active religious institution that hopes to leave visitors with a positive impression of Quakerism.

by Katelyn Hobbs, University of Pennsylvania

The Betsy Ross House

239 Arch Street

Welcome to the Betsy Ross House, the museum that celebrates the legendary maker of the first American Flag! Supposedly, rooms in this colonial house, built in the 1740s, were rented by Betsy Ross between 1776 and 1779. Betsy, a trained upholsterer, ran a shop somewhere along this block of Arch Street, but it is unclear in which house she rented rooms. When I asked about this seemingly crucial discrepancy, the man working the front desk admitted that this house may not be the house, but it is styled as such and documents Betsy’s courageous efforts—does it really matter if this was the place where she lived and worked? Although I am unconcerned that the so-called "Betsy Ross House" may have never housed Betsy Ross, I have a feeling that tourists might find this upsetting. Apparently the Betsy Ross House curators agree because not a single text panel mentions any doubts about the house or its heroine.

Much like the house, the tale of Betsy Ross making the first American flag is unverifiable. In fact, the first time anyone outside Betsy’s family heard her story was in 1870 when her grandson recounted the events to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. According to the sworn statements of her family, Betsy often told them about the day when George Washington and two other members of the Continental Congress entered her upholstery shop. She invited them into her parlor, then Washington showed Betsy a sketch of a flag with thirteen red and white stripes and thirteen six-pointed stars. He asked her if she could make the flag. Betsy replied, “I do not know, but I will try.” As the story goes, Betsy suggested changing the stars to five-points rather than six because she could make a five-pointed star with a single snip of her scissors. They agree to the change. (If you tour the house, you will encounter Betsy in her upholstery shop—she will demonstrate how to make a 5-pointed star and explain the dangers of making an American flag. Betsy could have been tried for treason!)

Upholsterers did take in extra work making tents, uniforms, and flags for soldiers—and Betsy was paid a large sum of money from the Pennsylvania State Navy Board for making flags in 1777, but most scholars do not believe Betsy’s story. On their website, the Betsy Ross House briefly acknowledges this skepticism, writing: “So, historical fact or well-loved legend, the story of Betsy Ross is as American as apple pie. After your visit, decide what YOU believe!” Regardless of its historical accuracy, the Betsy Ross House tells the story of Betsy’s patriotism with concise text panels, a real-life Betsy Ross, the only interpretation of an 18th century upholstery shop in the country, and several interactive experiences for guests. There’s a kid’s scavenger hunt and play kitchen. There are audio guides for all ages. And there is even a hot-chocolate scent machine in the recreated kitchen—after all, patriots didn’t drink British-taxed tea, they either drank hot chocolate or coffee!

By 1876, this building was generally recognized as the place where Betsy Ross lived when she made the first American Flag. During the 19th century, the Munds, a German immigrant family, ran several businesses from the house. They took advantage of the house’s interesting history by posting a sign on the outside that read: “First Flag of the US Made in this House.” By the end of the 19th century, most of the other colonial houses on Arch Street had been replaced with industrial buildings. Many people feared that the Betsy Ross House would meet the same fate. In 1898, a group of concerned citizens established the American Flag House and Betsy Ross Memorial Association to raise money to purchase the house from the Munds, restore it, and open it as a public museum in honor of Betsy Ross and our first flag.

A few years earlier, Charles Weisgerber, one of the founding members of the Memorial Association, painted the iconic Birth of Our Nation’s Flag—a 9 x 12’ painting depicting the scene of Betsy Ross meeting the flag committee in her parlor. He won first place and $1000 in a statewide competition, then his painting traveled to Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition—spreading the Betsy Ross legend. In efforts to save the Betsy Ross House, the Memorial Association sold lifetime memberships for 10 cents. Each donor received a certificate imprinted with an image of Birth of Our Nation’s Flag. Two million dimes later, and Weisgerber and the Memorial Association bought the Flag House. Weisgerber and his family moved into the house in 1898 and immediately opened two rooms to the public—one was a souvenir shop, the other was designated the place where Betsy met with the Flag Committee. Weisgerber was so patriotic that he named his son Vexil Domus, which is Latin for “Flag House.”

By 1937, the house was in dire need of restoration work. The Philadelphia radio mogul A. Atwater Kent offered to pay up to $25,000 for the restoration. Historic architect, Richardson Brognard Okie was commissioned to do the work. Okie spared the house’s original architectural elements wherever possible. Construction was completed and all eight rooms of the house were open to the public on Flag Day, June 14, 1937. Kent also purchased the two adjacent properties to the west of the Betsy Ross House to develop a “civic garden.” The entire property was given to the city in 1941. In 1974, the courtyard was renovated and the fountain was added. Two years later, the remains of Betsy and her third husband John Claypoole were moved from the distant Mount Moriah cemetery to the garden on the west side of the courtyard...though it’s unclear if the remains buried here are actually Betsy’s...

Both inside and out the Betsy Ross House presents itself as a famous place. Not only is it the only colonial building on the block, it is also festooned with big red-white-and-blue flags! You’ll also notice that there is a Betsy Ross House sign, a historic monument plaque, and the Betsy Ross House is listed on street signs with arrows. Furthermore, the Betsy Ross House courtyard more than doubles the site’s footprint and opens up the space in a tightly packed historic part of the city. Inside, there is a new exhibition entitled “A Museum in the Making: The American Flag House & Betsy Ross Memorial Association, 1898-1941.” Through archival photos and one-of-a-kind museum artifacts, visitors learn how everyday citizens came together to transform a humble home into a treasured landmark. Notably, guests begin their visit by entering through the richly colored and welcoming gift shop which announces this place as both important to see—and “souvenir worthy.”

by Kendra Grimmett, University of Pennsylvania

Elfreth's Alley

126 Elfreth's Alley

Elfreth’s Alley is purportedly the oldest continuously inhabited residential city block in the United States. Its thirty-two houses date from the 1720s to the 1830s. It has been described as the best preserved colonial street in Philadelphia, both in architecture and scale. Elfreth’s Alley is considered to be the closest approximation of a seventeenth century Philadelphia streetscape.

The alley was established around 1702 by two blacksmiths, John Gilbert and Author Wells, presumably to give their smitheries, located along the Delaware River, easier access to 2nd street, a primary trade route for goods throughout the region.

Though the alley was known by several different names during the first half of the eighteenth century, by the 1750s it was generally referred to as Elfreth’s Alley. This name comes from the prosperous blacksmith Jeremiah Elfreth, who acquired land on both sides of the alley, near 2nd street, from two of his five wives, both of whom were related to John Gilbert. Most early inhabitants were craftsmen who rented their homes, usually only for a few years before moving on to other residences. Some examples of early inhabitants include William Maugridge, a friend of Benjamin Franklin, who lived in number 122 in 1728. Matthias Meyer, a German potter from Hilsbach, purchased number 199 in the year 1757. Moses Mordechai, a founding member of the synagogue Mikveh Israel, was a tenant in number 118 in the year 1769.

Today, the Elfreth’s Alley Association Museum occupies numbers 126 and 124. Number 126 was built and sold by Jeremiah Elfreth to Mary Smith and Sarah Milton, two highly regarded mantua makers (dress makers), sometime in the 1760s.

The Elfreth’s Alley Association was founded in 1934 to preserve the historical character of the block. Also during the 1930s, residents of the Alley began opening their homes to the public one Saturday in June, a celebration known as “Fete day.” In 1948, a publication by the American Association for State and Local History reports that the EAA was collecting money to aid in preservation efforts. The language of the statement implies that the EAA was not yet receiving any public support. Their efforts succeeded and in 1960 the alley became a National Historic Landmark.

Today the block is touted in tours of Old City and is counted among Philadelphia’s famous historic landmarks. It even makes an appearance in the popular children’s book Good Night Philadelphia.

by Harrison Schley, University of Pennsylvania

City Tavern

138 South 2nd Street at Walnut Street